Once upon a time, in the late 1920s, Speculator was the location of the most famous boxing training camp in the world. Gene Tunney, world heavyweight champion, trained there during the most momentous time of his career.

Following Tunney's successful acquisition and defense of his championship, such acclaimed boxers as Max Baer, Max Schmeling, Maxie Rosenbloom, Jim Slattery, and Knute Hansen were eager to train there, too.

For several years, there were famous boxers all over Speculator.

The sweet science

Boxing is nicknamed "the Sweet Science," a phrase which originated with Pierce Egan, a British sports journalist of the early 1800s. He wrote a famous series of boxing articles collected in five volumes, collectively titled "Boxiana." Throughout the articles he called boxing the "Sweet Science of Bruising." Another writer, AJ Libeling, was to publish a mid-20th century collection of boxing articles which he named "The Sweet Science" in honor of the phrase. Sugar Ray Robinson and Sugar Ray Leonard both received their nicknames from its wide use.

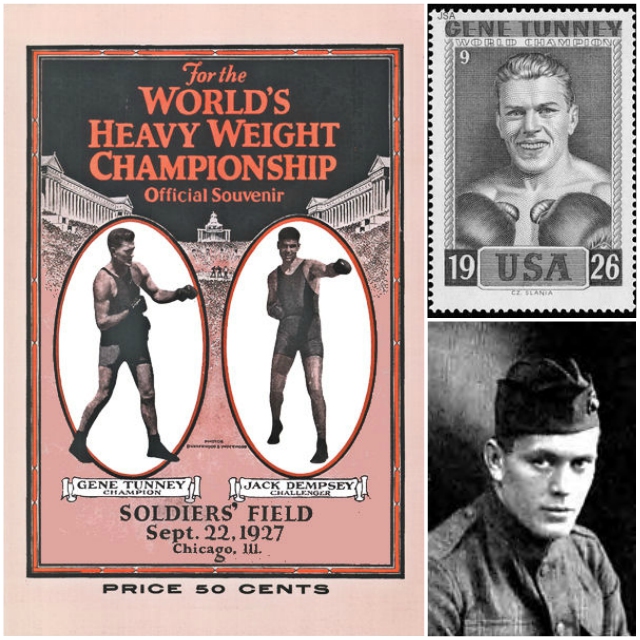

It has been nearly a century since the famous Tunney-Dempsey fight, and it is easy to lose track of what an enormous event it was, worldwide. Boxing was huge during the Roaring Twenties. The National Boxing Association was formed in 1921, by leading promoter Tex Rickard. He was the P. T. Barnum and Don King of the time.

The matches drew thousands to arenas. They were covered by journalists and newsreel cameras as boxers became sports heroes of the day. Jack Dempsey, world heavyweight boxing champion, was ranked with Babe Ruth (baseball), Red Grange (football), Bill Tilden (tennis), and Bobby Jones (golf), as one of the "Big Five." There were boxing celebrities from every continent, from the United States, England, Germany, and France, but also Argentina, the Philippines, and Senegal.

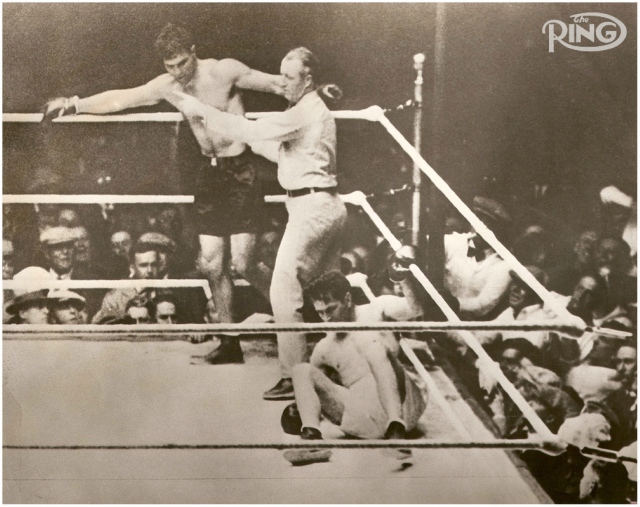

In 1926, Jack Dempsey had been Heavyweight champion for seven years, lionized for his trademark aggressive fighting style, which was characterized by powerful punching. So when a contender appeared, the world went wild.

Back to nature

The contrast couldn't have been greater. Jack Dempsey was the "The Manassa Mauler," who had learned his pugilistic skills by appearing in bars and declaring he would take anyone on. He made his living from the bets which would ensue. Speaking of a pivotal 1914 fight, he recalled, "In those days they didn't stop mining-town fights as long as one guy could move."

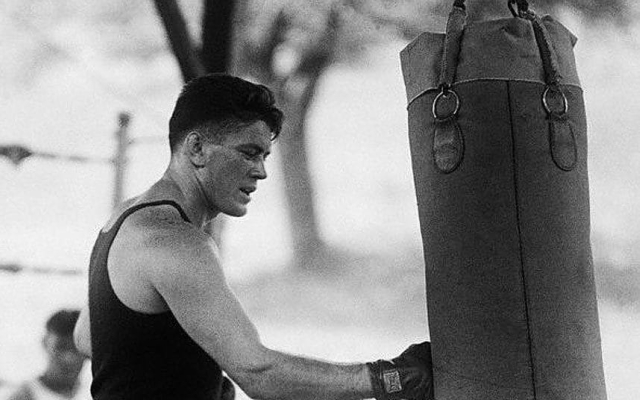

Gene Tunney was known for being a bookworm when he wasn't being a boxer. He had joined the US Marines in WWI and fought in the ring more than the trenches once his commanding officers discovered his skills. He was the champion of the American Expeditionary Forces and a "thinking" fighter. Fancy footwork and defensive strategy were what he was known for, a fighter who worked the ring like a chess player.

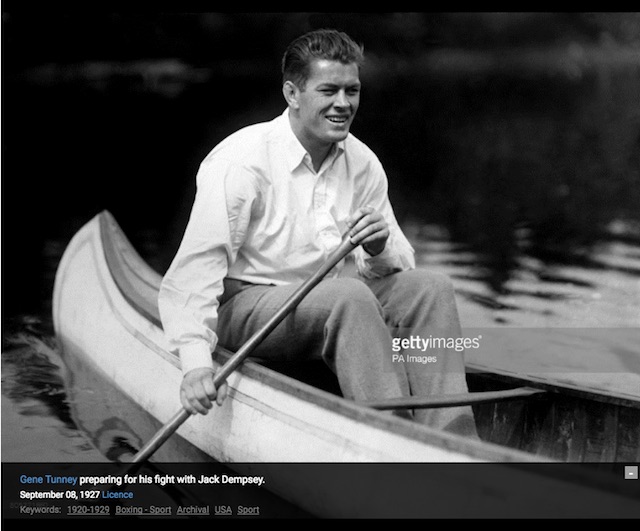

A fellow Marine, William Osborne, had two hotels and some tourist cabins in Speculator. He invited his friend to train there. The fresh air and lack of big city distractions would help him train for this important fight, and it would bring publicity to his business. So Gene Tunney, born in NYC, took to the outdoor life.

He found it to his liking, drawing on a previous experience where had spent the winter of 1921 as a lumberjack in northern Ontario. He told a reporter in a September 28, 1926 interview that he was "wanting the solitude and the strenuous labors of the woods to help condition himself for the career that appeared before him."

Whatever he did paid off spectacularly. He won the 1926 championship, even with the famous "Long Count" incident as a factor. Dempsey had knocked Tunney down, the first time Tunney had ever gone down in a boxing match. But Dempsey did not remember to follow a new boxing rule that required him to move to a neutral corner of the ring before the count could begin. Tunney bounced back and won the match.

He was the new Heavyweight champion.

Tunney was to defend his title once more, in 1927, before his retirement. Still, for several years more, the training camp in Speculator remained a popular spot to train. It attracted many other boxing personalities and the celebrities who liked to hang out with them. Tunney's boxing retirement in 1928 took some of the cachet from the camp, and by the time the Great Depression created upheavals throughout the country, it feel into quiet disuse.

memories linger

One such unlikely boxing fan was Nobel Prize winning playwright George Bernard Shaw. One of Gene Tunney's sons, Jay R. Tunney, wrote a book, "The Prizefighter and the Playwright," about the seemingly improbable friendship between his father and Shaw. Shaw, himself a former amateur boxer, declared Tunney a "scientific boxer," and that this would be a promising way to triumph over the might of the hard-hitting Dempsey.

Tunney, who declared that Shaw was his literary hero, shared his training camp reading list with a reporter. It included such luminaries as Shakespeare, Jack London, H.G. Wells, Thornton Wilder, and Samuel Butler's "The Way of All Flesh." There was much open skepticism, but it wasn't a publicity stunt at all. As a boy, Tunney had started his boxing career by defending himself against bullies who had found his intellectual ways objectionable.

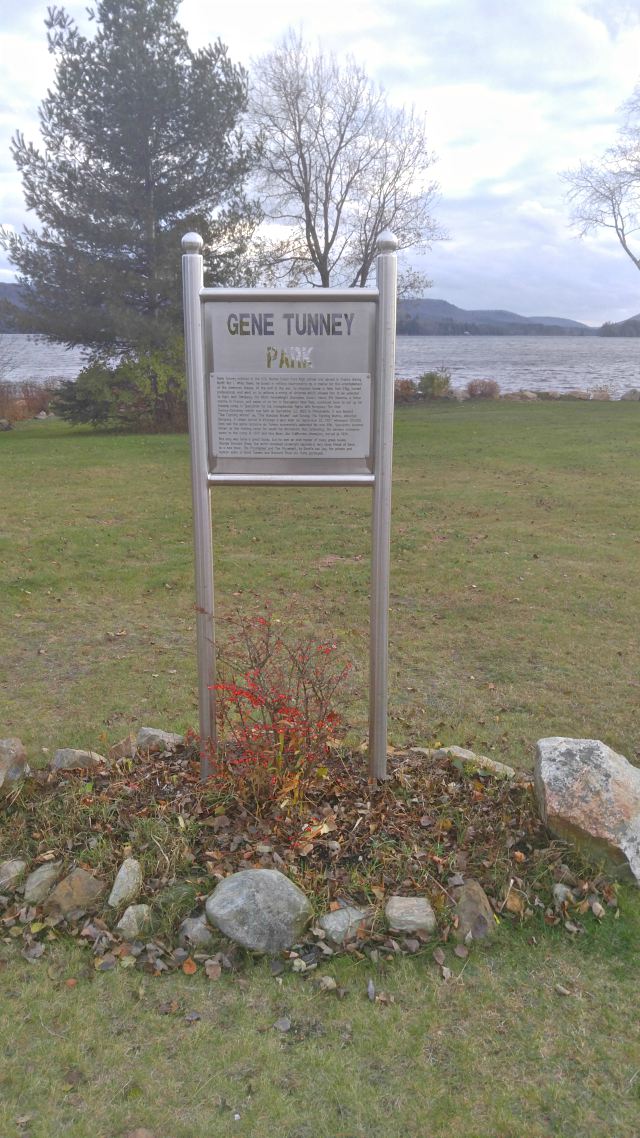

Even with such a short boxing career, the memories remained bright. In 2014, on a site formerly occupied by one of the hotels of William Osborne, Gene Tunney Park was dedicated.

Jay Tunney, one of Gene Tunney's sons, attended the park dedication. He told a local newspaper, "My father was undistracted in Speculator. That was the best part. He could think of things and clear his mind and have things the way he wanted."

He confirmed the newspaper stories. When his father was not training, he was reading. The calm and beauty of the Adirondacks was helpful to him.

And that part has not changed one bit.

Choose some fun lodging. Eat like a champ with our dining. Explore more interesting history.